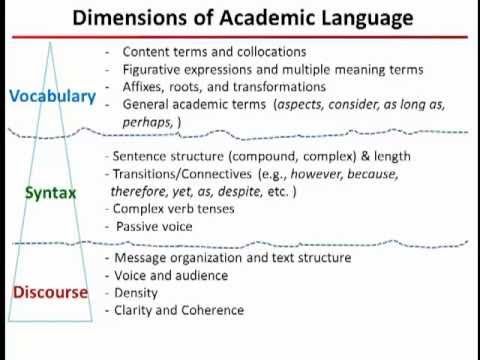

3 Dimensions Academic Language

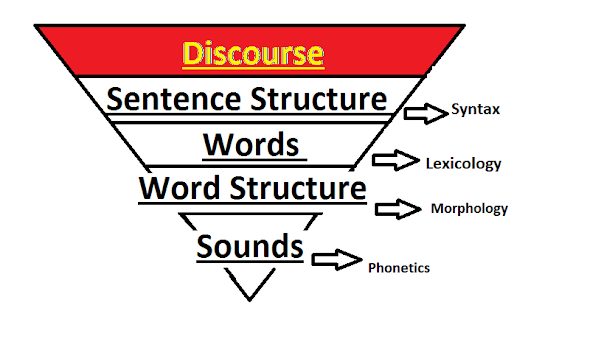

Academic Language is not only content vocabulary, it includes wide range of specific vocabulary items, grammar and syntax constructions, and discourse features.

Vocabulary consists of words and phrases, including general academic vocabulary that students may encounter in a variety of content areas, specialized academic vocabulary that is specific to a content area, and technical academic vocabulary necessary for discussing particular topic within a content area.

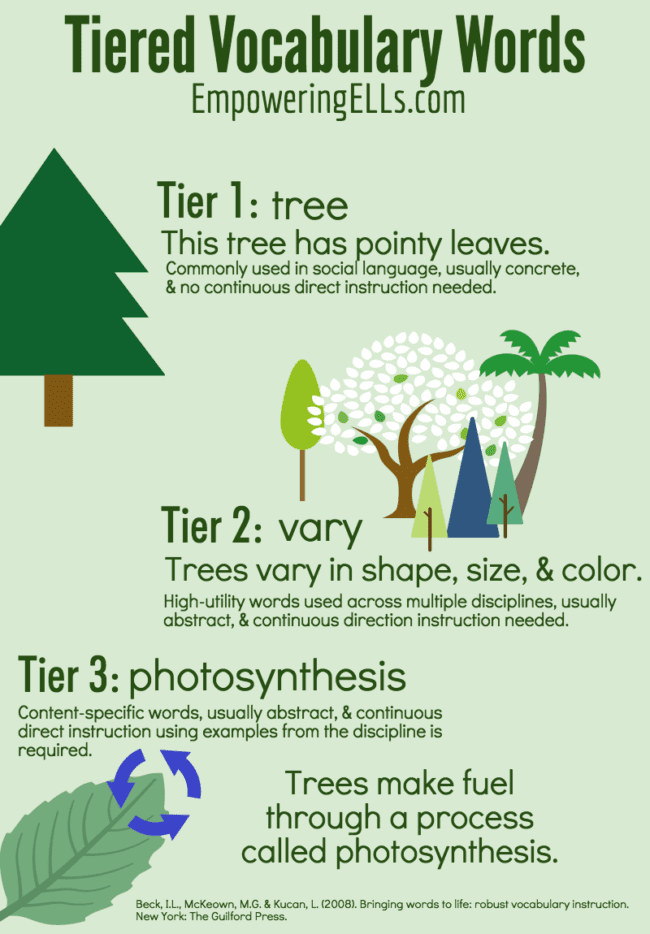

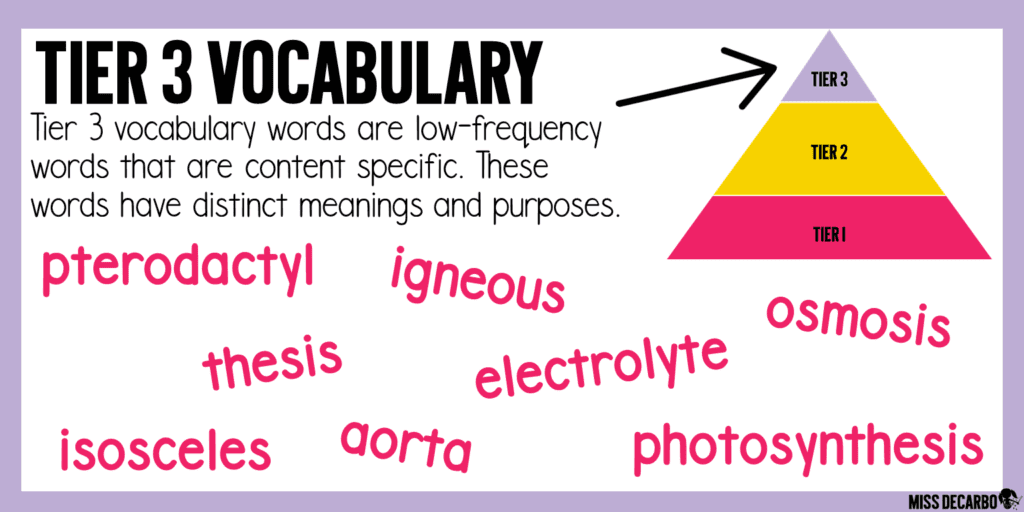

There are three tiers of vocabulary.

Research has shown that vocabulary development plays the most critical role in ELs’ language acquisition and academic achievement (August, Carlo, Dressler, & Snow, 2005; Chung, 2012). But in current practices, what vocabulary do I need to teach? According to the article “Tiered Vocabulary: Not All Words are Created Equal” by Tan Huynh, he suggests “the concept of the Tiered Vocabulary Words (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2002). Words carry different weight. Choose the ones that tip the academic scale . Some are concrete, non-abstract words that do not need direct instruction, like the words “bathroom” and “trees”.

Tan teaches Tier 1 vocabulary this way:

“We were reading Patricia McCormick’s Sold during a unit where we explored the concept of “family”. As we were engaged in Visible Reading (my version of guided close reading), we stumbled onto the word “thatched”. Below is my dialogue with the students illustrating how I teach Tier One words in context.

Stephanie: “What’s ‘thatched’?”

Mr. Tan: “What strategy can we use?”

Army: “Translate” (and yes, I have a student named “Army”).

(Everyone goes to their devices and Google translates “thatched” in Korean, Laotian, Chinese, German, Thai and Japanese.)

Moji: Wait. I don’t get it. (Google Translate sometimes helpful, and when it’s not, we use a different strategy. I try to encourage Google Translate as a first step for vocabulary because it honors my ELs’ home language and it’s an efficient step).

Jake: It’s like, like something with straw.

Stephanie: Google Translate doesn’t have Papua New Guinea.

Dexter: I know how to say it in Lao but can’t describe it in English.

Mr. Tan: So what’s another strategy?

Stephanie: Google Image

(They return to their laptops to search “thatched” in Google Image. Then they understand the word and we move onto the reading.)

Yeah, I could easily have told them the word, and we would have moved onto the reading faster. However, my teaching philosophy emphasizes solving problems and developing transferable skills to foster literacy independence, not rote memorization. “

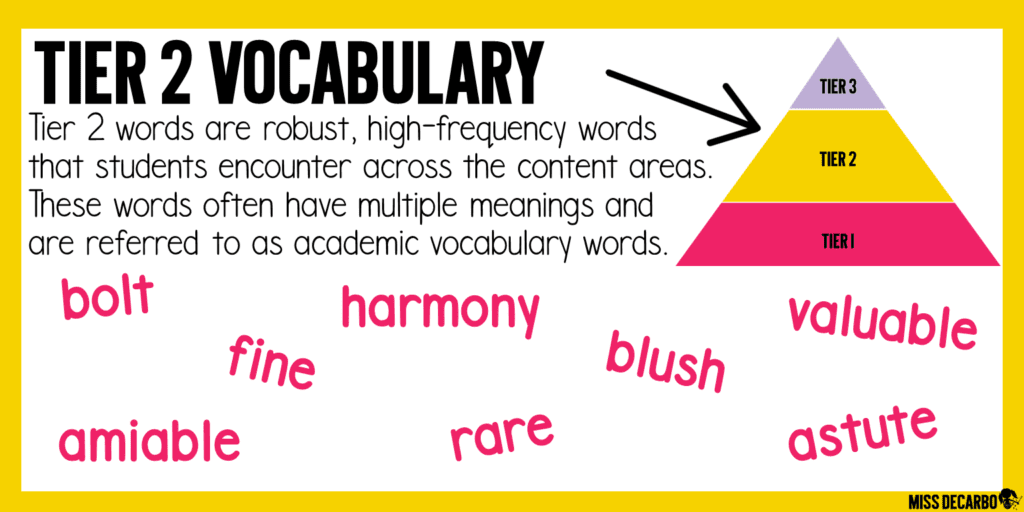

According to the article “The Three Tiers of Vocabulary for Classroom Instruction”, author Miss Decarbo notes “Tier 2 vocabulary words are robust, high-frequency words that students encounter across the content areas. They are not widely used in speech and daily conversation. Unlike Tier 1 words, Tier 2 words are not usually learned naturally or independently, because students do not hear or use them in conversation. A key point to understand is that Tier 2 words are often used and found in books and written text. Tier 2 vocabulary words often have multiple meanings. This tier can also be referred to as academic vocabulary words. Examples of Tier 2 vocabulary words are listed in the image above.”

Tier 3 words have a distinct purpose, and we only use them when they relate to a specific topic or domain. When we use a Tier 3 word, there is a specific reason to do so, such as when we learn about plants in a science unit or triangles during math class.

According to Miss Decarbo, she suggests “As teachers, we will get the most “bang for our buck” if we spend the bulk of our vocabulary instruction on Tier 2 words. These are words found and used across a variety of topics, domains, areas, and content. Since MANY Tier 2 words have multiple meanings, they are more difficult to learn, because students need to understand the word within multiple contexts, as well as understand the connection between the words’ synonyms and antonyms.”

Each content area often has unique ways to organize and present language at the sentence level, in addition to vocabulary. The complexity of language structures may be more easily recognized in written form, such as content area textbooks.

According to Academic Language Mastery: Grammar and Syntax in Content book, authors Dr. David E Freeman and Dr. Yvonn Freeman suggest that when instruction applies to student writing, it helps them produce more effective pieces. Students need many opportunities for meaningful writing.

Dr. David Freeman and Dr. Yvonn Freeman give a practical application to the classroom using the sentence frame strategy. A 4th grade classroom teacher helped her students write complex sentences by using sentence frame.

4th grade students finished reading Manana Iguana, a story based on the familiar little red hen folktale. The teacher chose this book because students lived in the rural area in the Southwest where Iguana were common.

4th grade teacher divided students into groups. Each group was given a vocabulary word like disappointed, frustrated, or exhausted. They were also given a sentence frame:

“Iguana was ____________ because ___________________.”

The groups completed their sentences using their vocabulary word, and then supplied a reason.

Groups Examples:

“Iguana was frustrated because she had to do all the work.”

“Iguana was depressed because nobody would help her.”

When students finished, the group put their sentences on sentence strips and inserted into a semantic Web chart so all students could see.

Authors also believe sentence frames are a good way to scaffold students’ development of more complex syntactic structures. A third grade teacher taught a unit on Africa. Students chose a country to research, and then developed a travel brochure to attract people to the country. Students received sentence frames for each of the paragraphs in the brochure.

“You should travel to _________ because ________________.”

Students completed this sentence by listing three reasons someone should visit their country. The teacher gave students sentence starters, such as “First of all _________________.”, “Another Reason _______________.”, and “Finally ______________________.” to help structure the remaining paragraphs. This scaffolded instruction enabled students to write well-structured travel brochures.

According to the article “How Rich is Your Classroom Discourse?” By: Jelani Jabari notes “In the average classroom, as much as 70% of instructional time consists of these kinds of verbal exchanges between you and students or among students: teacher initiation, student response, teacher evaluation of the response/feedback. Classroom discussion, dialogue, and discourse are the principal means of exchanging ideas, evaluating mastery, developing thinking processes, and reflecting on content and shared thoughts.”

Jabari suggests there are three elements of rich discourse in the classroom: by discussing what is rich discourse and how students benefit from it. Second element is embedding the spirit of collaboration versus competition. Classroom talk is not only a means for students to support each other, but also to hold each other accountable by helping clarify, restate, and challenge ideas. A third central element of developing a culture that fosters rich discourse is helping students appreciate the processes to get there, versus simply the production of right answers. Make it clear that you value students strategically thinking about, discussing, clarifying, and elaborating on ideas, rather than having someone simply state the correct answer to save time.

Jabari also discusses the use of complex thinking strategies, such as making claims supported with evidence and reasoning, discerning the author’s purpose and its effect on the interpretation of text, and applying models to tasks. If you want more information on how to engage students in complex thinking strategies, you can go to https://www.amle.org/how-rich-is-your-classroom-discourse/

Conclusion

Authors Joy L. Egbert and Gisela Ernst-Slavit of Access to Academics emphasize that “academic language involves more than terms, conventions, and genres. In other words, the teaching and learning of academic language requires more than learning various linguistic components. It involves cultural knowledge about the ways of being in the world, ways of acting, thinking, interacting, valuing, believing, speaking, and sometimes writing and reading, connected to particular identities and social roles.” (pg 11)

The next blog will use a unit on Natural Disasters to teach language and content.

Reference

Beck, I.L., McKeown, M.G. & Kucan, L. (2008). Bringing words to life: robust vocabulary instruction. New York: The Guilford Press. Beck, I. L.

Chung, S. F. (2012). Research-Based Vocabulary Instruction for English Language Learners.The Reading Matrix,12(2), 105-120. Retrieved from http://www.readingmatrix.com/articles/september_2012/chung.pdf Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1998). What reading does for the mind. American Educator, 22(1 & 2), 1-8. Retrieved from http://www.csun.edu/~krowlands/Content/Academic_Resources/Reading/Useful%20Articles/CunninghamWhat%20Reading%20Does%20for%20the%20Mind.pdf

Decarlo. THE THREE TIERS OF VOCABULARY FOR CLASSROOM INSTRUCTION